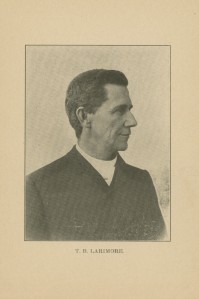

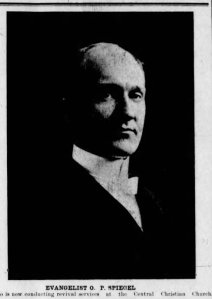

Pat yourself on the back if you made it through that last post. It was a bit of a slog. In my first two posts in this series, I tried to provide more historical context for the 1897 open letter exchange between T. B. Larimore and O. P. Spiegel.

What has troubled me—and the reason I wrote these pieces—has to do with the reserve,

O. P. Spiegel

the tight-lippedness, one sees in recent writers who have addressed the Larimore-Spiegel exchange. I have repeatedly asked myself, “Why?” Why is Spiegel only ever described as a former student of Larimore? Where does this reserve come from? Why does it continue to appear, as recently as that FB post by John Mark Hicks? What are we to make of it?

In this post, I want to suggest that the omission of details about Spiegel tells us something about the nature of history writing among Churches of Christ, as well as about the nature of the progressive-conservative dispute in mainline Churches of Christ.

****

Prior to the ’80s, information about Larimore circulated primarily in the three volumes of Letters and Sermons and in F. D. Srygley’s Larimore and His Boys, all of which were reprinted numerous times by the Gospel Advocate Company over the years. This is hardly surprising: Larimore has always had a following among the churches all across the doctrinal and theological spectrum. Almost a full century after his death, Larimore and his preaching still carry a power that others of his generation do not.

The situation changed, though, when Larimore came into focus for younger, progressive historians in ’80s and ’90s. Their output on Larimore is massive, and we won’t be able to address nearly all of it. But here’s a partial list.

- Pride of place must go to Douglas A. Foster, currently Professor of Church History and Director of the Center for Restoration Studies at Abilene Christian University. Foster published a book-length biography of Larimore, As Good as the Best, in 1984. He returned to Larimore in his 1986 Vanderbilt Ph.D. dissertation, The Struggle for Unity During the Period of Division of the Restoration Movement, 1875-1900. Larimore also plays a prominent role in the argument that Foster makes in his 1994 jeremiad Will the Cycle Be Unbroken?, and he appears again in Renewing God’s People, a history of the Churches of Christ that Foster co-authored with Gary Holloway in 2006.

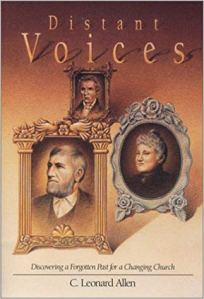

- C. Leonard Allen presently serves as Dean of the College of Bible and Ministry at Lipscomb University. In 1993, Allen published Distant Voices: Discovering a Forgotten Past for a Changing Church. Chapter 20, “How to Deal with Division,” focuses on the Larimore-Spiegel exchange.

- To this list, we should add Rubel Shelley. Shelley, of course, is not an academic historian, but his influential manifesto I Just Want to Be a Christian (1984) gives some attention to Larimore, and does so in a way that dovetails with the treatments found in Foster and Allen.

- Honorable mention goes to pugnacious progressive blogger Al Maxey. Maxey is hardly an academic historian, but his Reflections blog is widely distributed. In the June 20, 2008, issue he takes on Larimore, and dwells at length on the Larimore-Spiegel open letter exchange. As with Shelley, there is considerable overlap between Maxey’s goals and those of Foster and Allen.

All of these writers see something in Larimore, especially Foster. But what is it?

****

To answer that question, we have to remember the larger context in which these works were published: the conflict between progressives and conservatives that dominated the mainline Churches of Christ during the 1980s and 1990s. That conflict was defined by disagreements over several issues, perhaps the most prominent being grace, unity, the Holy Spirit, and hermeneutics. In an important sense, it was a generational conflict. Boomer progressives came into conflict with an older generation of leaders who, for a long time, had controlled the institutional centers of power in the church — the pages of the Gospel Advocate and the Bible departments of the colleges.

As they called for a re-evaluation of the theological consensus of the 1950s and ’60s, boomer progressives needed historical precedents in order to parry the sword thrusts of mainline conservatives. They needed a “usable past” (to borrow a phrase from recent historiographical studies) for progressives in mainline Churches of Christ. The historical work of Foster and Allen—but perhaps especially Allen’s Distant Voices—gave them that.

This purpose is explicit in Distant Voices. (This is important to note because I’m not accusing anyone of hiding anything, of being devious, or having a secret agenda.) Consider Allen’s words in Chapter 1:

This book is an exercise in remembering. It has one overarching purpose: to recover some of the forgotten or “distant voices” from the modern history of Churches of Christ.

I use the phrase “distant voices” in a double sense: first, “distant” simply in that these voices come from a time now long past; but second, and more importantly, “distant” in that they are the minority voices among Churches of Christ, the voices that have been drowned out, the softer, fainter voices. Some of the voices come from people largely forgotten by the tradition; others come from major, well-known figures who held certain views now largely forgotten.

We easily assume that the history of Churches of Christ is basically “the present writ small.” One may assume, in other words, that Alexander Campbell and his colleagues restored New Testament faith and order sometime in the early nineteenth century and that Churches of Christ—or at least some segment of them—have simply preserved that pattern of truth unchanged down to the present time. Today one may see a fairly fixed, uniform tradition and easily assume that this has been the story from near the movement’s beginnings.

But it was not. As the tradition formed through the nineteenth and down to the early twentieth century, certain voices assumed central, controlling positions, thereby pushing other voices to the margins. These more dominant voices shaped the tradition of the twentieth-century Churches of Christ. They set the boundaries of acceptable views. They defined orthodoxy. They also interpreted, shaped, and maintained the “memory” or story of the movement, and this shaped story made clear who stood at the center and who at the margins.

But these central, more powerful voices were not, simply by virtue of their power, necessarily the wisest or most astute. As Walter Brueggemann has put it, “the capacity to give authoritative interpretation [within a tradition] is a matter of social power, and not primarily a matter of insight or sensitivity.” Important insights may reside at the margins of a tradition as well as at its center, among the minority as well as the majority.

Churches of Christ are now in a time when the central or dominant voices of the twentieth-century tradition are being questioned—gently by some, more sharply by others. It is a time when many people are assessing their spiritual heritage, indeed, a time when the traditional settlement of center and margin is coming under critical review.

In such a time, it helps to hear some of the “distant voices,” those who once occupied a strong place in the tradition but whose views have been remembered selectively, screened out, or simply forgotten. Listening to such voices helps one glimpse a modern heritage that is broader, richer, and more diverse than one may presently suppose.

Out of such listening can arise a new and perhaps more faithful settlement of center and margin.

–C. Leonard Allen, Distant Voices: Discovering a Forgotten Past for a Changing Church (ACU Press, 1993): 4–5.

There is much to talk about here. (And some things to criticize: in particular, some of Allen’s postmodernist assumptions have passed their sell-by date.) Be that as it may, Allen’s larger aim of recovering “distant voices” shapes everything about the book. That’s not necessarily a bad thing. I think that Allen does a great service to the churches in highlighting what he chooses to highlight. Furthermore, historiography is never totally and completely objective. All of us who undertake to write history have our own agendas. Credit is due to Allen for being up front about his.

We have to acknowledge, though, that the context of the progressive-conservative fight colors the way he tells the story, especially when we come to the Larimore-Spiegel exchange. This is because, of course, Allen is not a neutral observer of the fight. He is a participant. His weapon is not the stinging article published in the Gospel Advocate, Wineskins, etc. It is the history that he is unearthing for his readers.

What does Allen see in the Larimore-Spiegel exchange? Simply this: Allen, and other progressives, sought to put on the mantle of moderation and simple Christianity that they saw in Larimore over against the spittle-flecked ravings of the mainline conservative editors and preachers, lectureship speakers and preaching school faculty members who opposed them. These were, to borrow Allen’s words, the voices who had “assumed central, controlling positions, thereby pushing other voices to the margins. These more dominant voices shaped the tradition of the twentieth-century Churches of Christ. They set the boundaries of acceptable views. They defined orthodoxy.” While others might be included, it is not difficult to see that Allen would have had in mind figures like Foy E. Wallace, Jr., and his disciples, generations now of dogmatic, hardline preachers and writers.

That’s the rhetorical frame Allen tries to establish in his treatment of Larimore. But there is a rhetorical sleight-of-hand at work in his treatment (or non-treatment) of Spiegel. To refresh your memory, here’s how Allen’s chapter on the Larimore-Spiegel exchange opens:

In July of 1897 the Christian Standard published “An Open Letter to T. B. Larimore” written by one of Larimore’s former students. The letter was full of admiration for Larimore and his work, but it contained an urgent request. “You owe it to yourself, your family, your friends, your Saviour and your God,” urged Oscar Spiegel, of Birmingham, Alabama, “to speak out on some matters now retarding the progress of the cause of Christ.” One cannot remain silent, he insisted, “when we see our fellow men, and especially our own family drifting apart.”

Spiegel then came to the point. He asked Larimore to declare himself on four key issues that were deeply dividing the restoration movement: the use of instrumental music in worship, the creation of missionary societies beyond the local church, attendance at “cooperative meetings,” and salary contracts for preachers.

“Thousands of your brethren and sisters,” Spiegel concluded, “believe it is your duty to speak out on these questions, and strive to unite, if possible, the people of God.”

—Distant Voices, pp. 153–54.

This is all that Allen says about Spiegel: he is “one of Larimore’s former students … [from] Birmingham, Alabama.” Why so little? We have already seen that there is plenty of information available about Spiegel.

Here’s my suggestion: By leaving Spiegel unidentified, the reader is left to his imagination, and might naturally assume that Spiegel was the 1890s equivalent of a writer for Contending for the Faith or the Spiritual Sword. After all, is it not usually those sorts of folks who make demands upon others to take a stand on the issues of the day? Indeed, we can almost hear Spiegel’s words

“You owe it to yourself, your family, your friends, your Saviour and your God, to speak out on some matters now retarding the progress of the cause of Christ.”

coming out of the mouth of an Ira Rice or a Buster Dobbs.

Interpreted in this way, Larimore’s words could be understood in a way that cohered with the aims of contemporary progressives. Allen and Foster’s readers clearly understood this. Maxey’s blog post on Larimore demonstrates this clearly. By appealing to Larimore, they could profess to be tired of doctrinal squabbles and internecine fighting, to be above the fray, and so forth. In keeping with this aim, Allen emphasizes Larimore’s unwillingness to fight:

Despite the strong and incessant voices pressuring him to take sides, he simply refused. Year after year, he refused. In many letters and sermons, Larimore made his conviction and practice clear. “My earnest desire,” he wrote, “is to keep entirely out of all unpleasant wrangles among Christians….I propose to finish my course without ever, even for one moment, engaging in partisan strife with anybody about anything.”

Accordingly, when someone asked him what “wing” of the church he belonged to, the loyal or the digressive, Larimore replied: “I propose never to stand identified with one special wing, branch, or party of the church. My aim is to preach the gospel, do the work of an evangelist, teach God’s children how to live, and, as long as I do live, to live as nearly an absolutely perfect life as possible.”

—Distant Voices, pg. 156

Allen highly praised these sentiments even as he was writing a book that was, in itself, a contribution to the squabbles he condemned. We could read Foster’s (and Shelley’s) work in a similar fashion. Maxey seems to have missed the memo, though. One of the funnier ironies of his work is how he uses Larimore—a man who, according to Maxey, “left behind a rich legacy of tireless effort to bring disparate disciples together in sweet fellowship rather than the partisan wrangling”—as a cudgel with which to beat John Waddey, the (now deceased) conservative editor of a (now defunct) journal called Christianity: Then and Now (according to Maxey, “a legalistic preacher for a small group of factionists in Surprise, Arizona”). This is not, I should say, meant to be a defense of Waddey. I’m simply highlighting Maxey’s peculiar appropriation of Larimore’s “rich legacy.”

Yet, shorn of their context, Larimore’s words to Spiegel are infused with a meaning that they did not originally possess. Once we understand who Spiegel is, the comparison that Allen and the rest were attempting to make falls flat. At the very least, it doesn’t apply with nearly the force that it might otherwise have.

****

O. P. Spiegel, as we have seen, was not a radical conservative editor. He was a vigorous young progressive, someone who strongly believed in the “fierce urgency of now” (to borrow a phrase from MLK that was used as the title of a CSC panel on “social change within the Churches of Christ” from a few years back). He aggressively sought to flip churches to his way of thinking in a way that any gal328.org or One Voice for Change sympathizer would recognize and admire.

As we saw in the last post, in the very year these letters were written, Spiegel, along with noted song leader J. D. Patton, had attempted to bring the organ into the Huntsville, Alabama, church. He failed, but his angry reaction to that failure—found in a letter that he wrote to the elders of the Huntsville church—is worth spending some time on:

This is an age of progress, development, and enlargement …. He [God] ordained that his people should use instruments of music in the old economy; they were never condemned in the new; they are used to illustrate the highest type of heavenly music and holy service in the world to come. In view of these facts and others, suppose I should play a weak brother, and say they must be used, etc.; then how about Rom. 14: 10–13; 15: 1, 2? In answer to these passages see Acts 5: 29. There is utterly no excuse for weak brothers in Huntsville in 1897, not if your eldership has done its duty. Of course if it encourages weak brothers in their slothfulness and ignorance by putting a premium upon them, you may always expect to have such members.

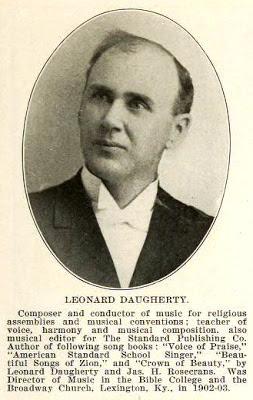

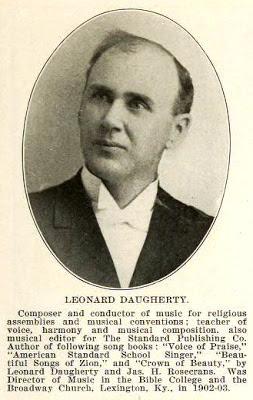

Yes, Brother Daugherty sung for you without the organ, but less than six months ago, on the streets of Nashville, he told me if the Lord would forgive him for so doing there, and several other places also, he would never do so again. He said no sensible musician would conduct the music unless the church would let him conduct it, and that no musician would risk his reputation by affirming that you could get anything like as good music out of an audience without as with an instrument. I tell you this is an age of progress, development, and enlargement, and what Daugherty did when an inexperienced boy away back in the eighties is no sign of what he will do in the nineties.

Yes, Brother Daugherty sung for you without the organ, but less than six months ago, on the streets of Nashville, he told me if the Lord would forgive him for so doing there, and several other places also, he would never do so again. He said no sensible musician would conduct the music unless the church would let him conduct it, and that no musician would risk his reputation by affirming that you could get anything like as good music out of an audience without as with an instrument. I tell you this is an age of progress, development, and enlargement, and what Daugherty did when an inexperienced boy away back in the eighties is no sign of what he will do in the nineties.

No, Professor [Patton] would not sing without the use of an instrument …. I have filed your letter for future use, as an official document from that church, refusing me the use of the house to preach in at my own charge. I stand thoroughly identified with the great bulk of the disciples who have fought so many battles and gained so many victories. When I make my report they shall of course set about to have some preaching done in Huntsville, as there seems not to be a single church in the city which stands for free thought and free speech.

(Quoted in F. D. Srygley. “From the Papers.” Gospel Advocate 39.43 (October 28, 1897): 673.)

This probably sounds familiar. All of the chief rhetorical strategies of the ardent young progressive of our own day can be found in these 120-year-old lines:

- The imperative necessity—indeed, the moral necessity—of change.

- The controlling rationale of progress. Or, more accurately, the confusion of the Holy Spirit with the Spirit of the Age (“progress, development, and enlargement”).

- “This is 1897!” (A statement which is identical in spirit to the young collegiate SJW who argues for her causes on the grounds that “It’s 2018!”)

When we read the Larimore-Spiegel open letter exchange with this in mind, it is Larimore who is the conservative in the equation, the cautious older man who was unwilling to buy in to the young firebrand’s aggressive program for change. And this was frustrating for Spiegel. So, in 1897, in his third year as State Evangelist in Alabama, Spiegel acted decisively to neutralize the influence that Larimore had in the churches of Alabama. He was nice about it, to be sure: the “Open Letter to T. B. Larimore” wasn’t openly hostile. But there was no mistaking what exactly Spiegel hoped to accomplish.

The 1890s were, as we’ve said, a decade of transition that witnessed a shift from one church with squabbling progressives and conservatives within her walls to two churches, two separate fellowships, rapidly moving apart from each other. In drawing the lines more definitively, Spiegel made a significant contribution to that process.

****

A bit of prognostication as we close. Painting in broad strokes. Take it, from an outsider no less, for what you think it’s worth.

When we consider the course of mainline progressivism since the early 2000s, I wonder if we are not seeing the beginnings of a generational divide between the boomer progressives of the ’80s and ’90s and their children, the millennial progressives of our day. The old battles about grace and unity and hermeneutics are in the past. Progressives and conservatives have largely gone their separate ways. Millennial progressives no longer engage in direct conflict with writers for the Spiritual Sword and similar publications. (Indeed, many are no longer aware of their existence.)

The issues have evolved, as well. The instrumental music question has been forcefully reopened in a way that it had not been in the ’80s. The questions surrounding women in ministry, beginning to be felt in the ’80s and ’90s, have come front and center over the past decade. Millennial progressives are motivated by a different set of concerns from those of their parents. Chief among these are issues of race and gender and sexuality—in keeping with the same issues that are currently roiling evangelicals as a whole. Indeed, a good many millennial progressives view themselves as part of the larger world of the evangelical left—not to mention the political left. They share many of the assumptions of this larger grouping; they mimic the same concerns about economic and social justice, gender equality, and the like. They draw their cues from figures like David Dark and Rachel Held Evans (to name just a couple), far more than from any representative figures from Churches of Christ. While there is much that is commendable in these new emphases (for example, the recovery of pacifism), there is much that is troubling, as well.

From a generational perspective, if boomer progressives looked to Larimore—gracious, patient, unwilling to take sides—as a suitable avatar for their own self-understanding, a significant number of their children could well find one of their own in O. P. Spiegel. His brash attitude and overweening sense of his own right-ness, manifested in the authoritarian tendencies seen so clearly in his letter to the Huntsville elders—and in his demand that his teacher come down clearly on the right side of history—calls to mind the forthright dogmatism, border-policing, and hyper-sensitivity of much theology emerging from the evangelical left in our own day. To what extent do these tendencies manifest themselves on the college campuses and the lecture circuits of mainline Churches of Christ?

I should say that Twitter is the petri dish from which I derive these observations. If Twitter is indeed an accurate reflection of what is and of what is to come, the spirit of O. P. Spiegel lives on among us much more fully than Leonard Allen could ever have imagined.

Finis.

36.180799

-86.736441

Yes,

Yes,