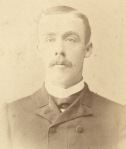

J. M. McCaleb (1862–1953)

By 1895, J. M. McCaleb had been doing independent mission work in Japan for more than a year. During that time he was a regular contributor to the Gospel Advocate, writing columns on a range of subjects from doctrinal issues to moral exhortations to book reviews to reports of the work in Japan. In the January 3, 1895, issue of the Advocate, he contributed a piece titled “Some Good Books” which contains short reviews of J. W. Shepherd’s Handbook on Baptism, J. L. Martin’s The Voice of Seven Thunders, and a new pamphlet by David Lipscomb titled “Truth-Seeking.”

I thought McCaleb’s comments on Martin’s book were interesting, and wanted to share them here:

I read this book some twelve or fifteen years ago, when a boy, but read it a second time with more interest and benefit, because better prepared to receive it. It is simply a commentary on Revelation given in the form of lectures. It is a very common idea that if one is not just a little “unbalanced,” he is at least wasting time in studying or preaching from Revelation. Hence this part of the Book is usually neglected. People take it for granted it is something not to be understood, so pass it by. In our Bible course of study at Lexington, I remember there was scarcely a hint at Revelation. Excellent as it is, I believe it could be improved by including this important part of the scriptures, if it was only to give a few leading points as to how it should be studied to be understood. While one may not agree with all the author says, there are certainly many excellent suggestions that stimulate one to study the last words of Jesus to the churches and the world with a new interest. Why call it a revelation if it is a mystery not to be understood?

(Excerpted from “Some Good Books,” Gospel Advocate 37.1 [January 3, 1895]: 6–7)

McCaleb, of course, was an 1891 graduate of the College of the Bible (in the same graduating class with O. P. Spiegel as it happens). This nugget of insight into the curriculum at Lexington helps us understand a bit more fully the disputes that broke out in the churches over premillennialism two decades later.