This is the second of two posts dealing with Irven Lee and his “A Friendly Letter on Benevolence” (1958). The first post provided a sketch of Lee’s life; this post will make some observations about the “Friendly Letter.”

Open division was a reality in Churches of Christ across the country in 1958. The controversy over institutions that had erupted in the years during and after WWII mushroomed by the middle of the 1950s into a heated and often very personal dispute. This is not the place for a complete timeline of the controversy, but it might be worth pointing out a few of the things that contributed to the atmosphere in which Lee wrote in 1958.

B. C. Goodpasture (1895-1977)

In December 1954, B. C. Goodpasture published with approval a letter written by an anonymous elder calling for a “quarantine of the ‘antis.'” This opened the door to, and gave sanction to, the kind of pressure tactics Lee references in the letter. A series of debates, each perhaps more acrimonious than the last, also began around this time: the Holt-Totty Indianapolis debate (October 1954); the Tant-Harper debates in Lufkin and Abilene, Texas (April and November 1955); and the Cogdill-Woods debate in Birmingham (November 1957). Perhaps more than anything else these helped solidify the identities of the two groups. None of this, of course, fully captures the mood in the churches in these years. Lots more could be said, specific incidents recounted, and so forth. It will have to suffice for the purposes of this piece, though.

At any rate, most contemporaries of these events would later point to the Cogdill-Woods debate (1957) as the final breaking point. For all practical purposes, there was no going back after this. Division was an accomplished fact. Knowing all of this, the tone and timing of Lee’s letter are surprising. That such a letter could be written in 1958 says something important. At one level, there was nothing in it for anyone on either side to try again, one more time, carefully and patiently, to reach across the ever-widening gulf between the two sides. But Lee tries, and that’s really significant.

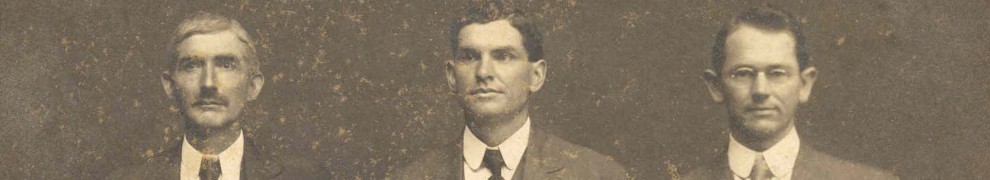

Irven Lee

The way in which he argues is also of great interest. Each of the debates listed above (and many others at the time) centered on the proper application of the traditional command-example-necessary inference hermeneutic. While it is clear that Lee accepts that hermeneutic and its assumptions, his arguments in this letter rely very little upon the hermeneutic. They proceed from other concerns. Several of those concerns, seen in the “Friendly Letter,” later recur in articles written for Searching the Scriptures as well as in his autobiography, Preaching in a Changing World (1975). I’ll briefly discuss the major ones here, drawing on citations from a variety of sources.

N.B. These arguments are closely interwoven in the texts themselves. My attempt to separate them out for analysis here is necessarily somewhat artificial. In other words, proceed with caution: go read the texts themselves.

****

1. First, there is the argument from history. For Lee, and many other non-institutional writers in the 1950s, there was a simple analogy to be made between the 19th century missionary society and the various cooperative schemes under discussion in their day. Lee focuses his attention first on the missionary society, before turning to issue of the orphan’s home. For Lee, “a study of [the missionary society’s] history is easy, and it illustrates every phase of the problem.”

The results of missionary society were not what its founders had intended: “The missionary society did not cause men to do more ‘mission’ work. It is evident as can be that the Christian church with its society has not grown as fast as the church has without it. The cooperative idea relieved the individual and the local church of much of their feeling of responsibility. They need not start new congregations since that would be done by headquarters. The society absorbed much of the money in costs of operation, and they cut the link between the congregation and the preacher on the field, so there was less personal interest in his work and less joy of accomplishment on the part of the congregation sending funds.”

Worst of all, for Lee, dogged support of the missionary society on the part of its staunchest advocates led to division. Conflict over support of colleges and Sunday schools also led to division. As Lee states, “These ‘good ideas’ were not good if they wounded the spiritual body of Christ. No more modern offering will be good if it divides the body of Christ.”

All of this, we should note, comes from a man who had been heavily involved with institutions for much of his career, in particular the schools for which he taught. Lee reflects on this at some length in his autobiography:

“I could not today [1975] get a job with three of the four schools where I have taught. I have made the point back through the years that I do not believe the church should give money into the school treasuries. During the thirties and forties I was generally commended for this stand. Today it is sometimes reported that I am against the schools when I say the same things. It has been heartbreaking to me to see these schools fall into the hands of those who cater to the liberal brethren among us” (Preaching, 20).

2. Second, Lee spends a great deal of time looking at the orphan’s home from (for lack of a better term) a human standpoint. It’s an argument from the heart, rather than from hermeneutics. Lee writes, “The most expensive and least desirable way to care for children is in the orphan’s home setup.” He then goes on to show the manifold ways in which, for all of the good intentions of those who work in them, orphan’s homes cannot provide the kind of care a child needs.

For example:

“One of the things a child needs is tender loving care. If one hundred children live in one big house, a given child may almost starve for affection and attention. He may make himself a nuisance in trying to get attention. If you will go to a so-called orphan home and sit down and put your arm around one child, another will come at once. There may soon be more than you can reach around. Some have had this experience and have gone away speaking of the good work of the institution in training the children to be so affectionate. It is more a matter of starvation. They are starved for this sort of attention…. In short, the child needs love. The very best matron cannot give this special attention to each of the children in her department” (Preaching, 76).

Of interest on this point is the fact that policy regarding the care of orphans in the United States has largely borne out his arguments (both in his day and since). He notes that states were already

moving away from institutionalized care in the 1950s — as were the mainline Protestant denominations who had gotten heavily involved at the turn of the century. Sociologists and government officials had already begun to show preference for foster care or adoption in all but the most extreme cases of mental illness or physical disability. By the time members of Churches of Christ jumped on board after WWII, institutionalized care was already falling out of favor.

3. Third, there is a critique of the tendency toward centralization in so many of the projects under discussion. Lee, and other non-institutional writers in the 1950s, feared the power that was accruing to the managers and boards of directors of the orphanages, schools, and other institutions: “The big church supported institutions dominate the churches that support them. They become a super government to ‘request’ and ‘advise’ by very effective means in many local affairs.” (One might think here of A. C. Pullias’ boast that no one could preach in a church in Middle Tennessee without his approval.)

And again: “Schools, publishing houses, and many other things have a right to exist as servants of mankind but not as a super government for the church or as a parasite on the church. The administrators of most of the colleges operated by our brethren have taken the very ‘liberal’ view of this crisis. I am embarrassed and ashamed of this. The constant need for funds brings them close to men of wealth. Those who are among the rich find it hard to have a child-like faith in the Lord’s plan. The temptation to trust in riches is evidently great. They made money by their own plans and they see the need of business (human) plans in the work of the church” (italics mine).

4.

Finally, perhaps the key idea in the whole argument, is Lee’s assertion that, in his words, “the Christian religion is a ‘Do It Yourself’ religion.” In other words, every Christian has a responsibility to minister to the needy. That responsibility cannot simply be outsourced (to use a contemporary term) to an outside agency. On the contrary, Lee and other North Alabama non-institutional writers insist on the importance of personal investment and sacrifice for the needy to the growth of faith. They advocate for a kind of “

lived religion,” a religion that does not separate doctrine and ethics, that recognizes the responsibility of the church to take care of its own. (All of these emphases can be found at an earlier date in the writings of David Lipscomb and James A. Harding.)

****

In the end, Lee urges his correspondent to continue to study, to love, to extend grace to those with whom he might disagree: “Love will do much to hold us together while the line between right and wrong comes into clearer view from more careful study of the scripture.”

It would be hard to say whether anyone on the pro-institutional side of the argument was swayed by this letter (we don’t even know what became of Lee’s friend, the addressee of the letter). Discussion had largely shut down on both sides by this point. That said, the letter was circulated so widely (in tract form) for so many years, I think, because it resonated deeply with many on the non-institutional side. It was patient and gracious, but full of conviction as well. It contradicted, without being hateful, the assertions of mainline editors and preachers that “antis” were “orphan haters” and “cranks.”

Nice overview of the letter. Brother Lee spent time in our home when I was a child. He was an important influence in my family and a godly man. One might wish for more examples of his gracious spirit today.

Thanks for stopping by, Joel. I’ve been nicely surprised in all of this to learn of just how many people’s lives have been touched by Lee.

Hope you are well.

Pingback: Irven Lee (1914-1991), Part I: Biography | Anastasis

Pingback: spirit of clarity or divisiveness « JRFibonacci's blog: partnering with reality

Excellent summary. I wish sometimes that the opponents of institutionalism who emphasized a less acrimonious approach to combatting it, such as Irven Lee, Bennie Lee Fudge, Granville Tyler, Harry Pickup Sr. and Jr., Robert Turner, etc. had had more influence. Perhaps it wouldn’t have changed much. since most brethren in the 50’s and early 60’s seemed to be in the “Church of Christer” mode and wanted a denomination.

Another early tract that I think zeroed in on the more basic issues beyond “authority for use of the treasury” was Harry Pickup Jr.’s tract “Institutionalism” which correctly pointed out that the more important issue was whether God’s church was a network of local churches or simply all the saved in the world.

Thanks. I’ve not seen Pickup’s tract. Do you happen to have a copy of it?

Thanks for your work, my friend. It helps my understanding and appreciation for non-institutional theology.

Your discussion was interesting to me. I would add a footnote to the historical section. When Foy E. Wallace, Jr., preached in the Music Hall Meeting in Houston, it was through a “sponsoring church” arrangement. Roy E. Cogdill was the preacher for the Norhill church which sponsored the meeting. But that is not the point I want to note. What is significant to me, from a historical perspective, is the statement by Cogdill in the introduction to “God’s Prophetic Word,” in which he said the meeting was conducted in this manner “in order that the meeting might be carried out on a sciptrual basis and without provoking criticism.” The significant statement here is that the sponoring church arrangement did not provoke criticism in 1945. To me, this belies the conclusion that it was an innovation by the mid-1950s.

Hi Alan,

Thanks for chiming in here.

My own read of Cogdill’s thinking, like Gardner’s, is that he changed his mind over time. Things (like the Music Hall Meeting) that didn’t raise any red flags for him in 1945 came to be seen as a threat only in the context of several years of rapid institutional expansion. Could we ask him, I think he might say that he could not have foreseen what would come of the sponsoring church arrangement he endorsed in 1945. Many were comfortable with the arrangements that did grow of it, of course; others, like him, were not.

That said, as I read the evidence of the 1940s and 50s, there was ongoing debate across the spectrum in the churches about exactly what constituted “institutionalism” with people landing at many different points in their conclusions. (One of my larger points in discussing the Irven Lee material is that there were different ways to be “non-institutional,” even in the 1950s.) That Cogdill changed his mind is perhaps not so unusual. The real problem was that there was a paper trail when he did so. As an editor, he did not have the luxury that others had of changing his mind without public consequences.

Again, thanks for your comments.

Brother Highers,

I’ve heard many good things about you and read some of your writings. I think your point is valid that Cogdill and some other well known NI names before and even after the 1950’s demonstrated “institutional” concepts at times. In other words, they tended to look upon Christ’s church as a movement, a collection of local congregations that came from the Stone-Campbell movement, rather than simply all the saved individuals in the world. The “Music Hall Meeting” certainly seems to demonstrate that concept, though Cogdill would have been loath to admit it. A similar point might be made regarding the fact that church support of orphans’ homes, though not promoted very strongly in the 1920’s and 1930’s, was generally unopposed until the 1950’s, if my understanding of history is correct.

I suppose it was the aggressive promotion of such ventures in the 1950’s and 1960’s that seemed to wake people like Irven Lee up to the fact that God’s church shouldn’t be treated like an alliance of local congregations with official adjuncts. It’s safe to say that Christians today still have to weed out sectarian concepts. It’s an ongoing battle. We can be thankful for God’s mercy!

Thanks to both of you for your comments. I agree that Roy Cogdill likely changed his mind about the sponsoring church arrangement which he endorsed in Houston in 1945. My point, however, is a historical one, namely, that Cogdill did not merely endorse the sponsoring church arrangement, but he also viewed it as a means of proceeding “without criticism.” This indicates that such an arrangement was not being opposed at the time, or at least Cogdill did not think so. This is an important fact in light of later charges that it was an innovation, departure, apostasy, etc. It seems to me that it was the opposition that was new, not the practice. We can be thankful that Cogdill’s contemporaneous observation helps put this matter into perspective.

Reblogged this on ἐκλεκτικός and commented:

This an interesting 2012 blog from Chris Cotten, which bears repeating in a time of renewed discussion among Christians who deplore the antagonism and alienation of the past. A first installment, also re-blogged here, provides some context.